Waiting to Inhale

As it’s Mental Health Awareness Month, I thought I should write about a nine-year-old boy's descent into madness. A little detour from my regular posts, but it may be of interest to anyone who found themselves in a similar situation.

I know the year must have been 1969, because I remember ‘Sugar, Sugar’ by The Archies playing on the hospital radio, and it was a new song I’d never heard before. I was sitting at a large round table with some other children and there was a pack of Kelloggs Cornflakes in the middle that looked unlike the regular packs my Mum used to buy. I guess it must have been a discounted pack specifically for hospitals because it was made of grey cardboard with minimal branding. The boy sitting opposite me was wearing a strange looking helmet made of rubber strips, and for a brief moment I saw his eyes flicker and roll back before his head plunged into his cereal bowl, showering me with milk.

There was a smiling little girl called Samantha who’d wheeled her way over to us on her little red plastic chair that had a scooped recess at the back to house her bulging deformed spine, and behind me was the hideous sound of gurgling. I turned to see a nurse trying to spoon feed a boy who was strapped to his wheelchair with white Velcro restraints. He clearly did not want to be fed and jerked his head around to avoid the spoon. He was a strange looking child, with the end of his nose and tips of his fingers missing.

Over in the corner left alone, and lying in a large cot was an emaciated looking boy with jet-black hair, wearing a diaper and the beginnings of teenage facial hair. He didn’t move. His eyes just stared soullessly at the ceiling.

I can’t remember what time of year it was, but as my Mum said goodbye I had a strange feeling that this ward would be my home for the immediate future, and as the days and weeks went by, the misfits became my friends.

I was in a bit of a daze to find myself in this strange place. It was only a couple of hours earlier that I’d been woken from sleep in a panic thinking I’d be late for school, but my Mum assured me that I needn’t worry because I wouldn’t be going to school today. I can’t remember if she told me why, but I do remember the car journey ending at the big iron gates with a sign that said Queen Mary’s Hospital for Children.

I already knew of the place because I’d been attending therapy sessions three times a week after school, with a kindly lady from New Zealand called Doctor Croke. My first session was something I later compared to a scene in Escape from the Planet of the Apes, where Dr. Zira is given different shapes to slot into various holes, and many other intelligence tests.

I wish now that I could remember all that was said during my meetings with Doctor Croke, because whatever technique she applied, she managed eventually to ease me back to normality. In later years my mother told me I had what was then known as Severe Obsessional Neurosis.

My mother must have been at her wits end trying to understand what was going on with me, and finally compelled to seek assistance from social services. I remember one lunchtime sitting up at the table with my family dressed in only my vest and underpants and eating a lettuce sandwich, when a rather old-fashioned looking woman turned up, obviously on a well-timed observational mission.

To explain why I was eating lettuce sandwiches in my underwear I need to explain that by this point I was trying as best I could to avoid eating anything, and food just seemed like contaminants in their early stages that I didn’t want to get on my clothes. Any trips to the bathroom would result in extensive washing that usually took at least 30 minutes, after which I would go straight to the couch and lie there, avoiding touching anything, especially my toys, lest they’d be contaminated. My decontamination process would last until the following morning when I could resume my far from normal life. By now this included the good voice and the bad voice telling me what, or what not to do, and this could become even more disorientating when the bad voice pretended to be the good voice.

Washing after peeing wasn’t quite as time consuming as the other, but it meant that my legs were permanently chapped, and short trousers became painful to wear. My theory about not eating meant that I could go for days without having to go to the loo. In fact I decided I would only allow myself to go on Fridays. This I’m sure caused irreparable damage to my system, but I really had no choice, and trying to make it through to Friday became an incredible challenge.

Another thing that became problematic was reading my favourite comics, because it began to affect my breathing. If I was reading Spider-Man’s word balloons for example, I could breathe in, but if I was reading the Green Goblin’s word balloons I’d either breathe out, or hold my breath for fear of inhaling his innate evil. Lengthy word balloons were a trial.

I know, I know this all sounds completely nuts, but that is exactly why I was sectioned at the age of ten, until I was well enough to return home to my family.

The numbers thing was also prevalent. At first I’d touch a doorknob three times, then six, then nine, then twelve. I don’t think I got beyond twelve, but everyday life was pretty hellish.

Old people were a problem for me too. I can remember a planned family trip to see my Grandfather and how I jumped out of the car to avoid going. My parents ran after me to get me back into the car. I can’t imagine what my grandfather thought of me as I pressed myself up against the doorframe and refused to go into the living room. The entirely logical reason for this was that he was old and decaying, and I really didn't want to be infected by his disintegration.

I know my mother had been called to my school to speak with the teachers who’d found my behaviour incredibly odd. In English class we’d be asked to write an essay, and I’d write maybe two or three words and just daydream the lesson away. There was an imaginary thing called ‘The Lurgy’ that the kids used to tease each other about, and tap each other on the shoulder to pass it on. I began to believe it was real. There were some unfortunate kids who obviously came from a poor background, a sister and brother. They were cruelly known as the Stinky McClarences, and they had seldom washed, hand-me-down clothing that looked like it originated in the 1940s. One day, the older brother chased me around the playground, eventually catching up with me and smothering me with his smelly clothing, I was absolutely terrified, and convinced I’d caught the lurgy… whatever that was.

Superstition played a big part in my life too. If you don’t touch that thing three times, someone will die. Don’t cross a bridge while a train is under it. Don’t tread on the lines in the pavement — that made things difficult. In fact everything became difficult. But however bad it seemed, my problems paled in comparison to the kids in my ward.

Samantha, a lovely happy child with Spina bifida, who could only get around in her little plastic wheelchair. The kid with the rubber helmet who would just keel over at any moment. Another kid (I can’t remember all of their names) who had a dressing on his chest covering a hole with a green thing poking out that the nurse would push back in every now and again. Then there was Troy. One of the nurses absolutely adored Troy, and told us she was trying to adopt him. Troy was the most unfortunate of us all to my mind. The kindly nurse told me he’d been abandoned in a telephone box as a baby and had lived all his life at Queen Mary’s. Troy couldn’t talk because he’d bitten his tongue off, which led to the removal of his teeth. Before that he’d managed to attack the ends of his fingers and his nose. This was why Troy was restrained in his wheelchair all day long, and strapped down in his bed at night. I know this sounds horrific and unbelievable, but apparently it’s an incredibly rare genetic condition called Lesch-Nyhan syndrome.

The weird thing is, that the longer I got to be with these children, the less abnormal they seemed to be, and now I tend to think this was the whole point of Doctor Croke placing me there. My neurosis made me seek perfection in everything. A slightly chipped toy became useless and unwanted. I didn’t like the fact that my mum wore glasses, I saw it as an imperfection. Everything had to be orderly. I remember trying to copy a photo of Illya Kuryakin from The Man from UNCLE as a pencil drawing, but I couldn’t get it to look like a photo and the frustration that caused me was immense.

Because I wasn’t attending school, there was a teacher who came to the ward to keep us occupied with some kind of learning. I also drew in my sketchpad quite a bit. I didn’t have many toys with me except for my favourite Wham-O Master Tournament Frisbee that my aunt had brought over from Canada. I was allowed just outside where there was grass and a few trees. I know I was there during late summer because I used to aim my Frisbee at piles of Autumn leaves and pretend it was Lost in Space’s Jupiter Two crash landing. I also remember we had Halloween in the ward and a painting competition. I painted a horrific face that freaked me out so much they took it down. I had a Pinocchio Pelham string Puppet hanging next to my bed, and when the kindly nurse saw it, she said she’d bring me one of hers to keep Pinocchio company, and she did. Hers was the Swiss character, Heidi, and she let me keep it.

The one thing I did request my parents to bring me was a pretty realistic joke-shop dog turd from my toy box. I had plans, though I didn’t tell them what they were. Late one evening when the lights were dimmed, I got the other kids out of bed, including Samantha, but not Troy. That would have been problematic. The tungsten lighting from the night nurse’s office was glowing visibly, as we crept up and peered through the window, waiting for her to leave the room. I then snuck in and placed the fake turd on her desk, and we waited, giggling. Rubber helmet boy managed not to keel over, and eventually she returned to her office and screamed! I did get into trouble for that the following day in the form of an enema. I can’t think there was any other reason for it, but it put me off any other antics, that’s for sure.

One day a newcomer arrived and was given the bed next to mine. His name was Kevin Dudley. I know this because I still have the signed drawings he did in my sketchbook. I think he was only a year older than me, and artistically very talented. We got on incredibly well. I have no idea what he was ‘in for’ and never asked, but physically he seemed fine.

At some point his father turned up with a bloody great model boat and installed it on his nightstand. I’d never seen anything like it. It had little windows that would light up, and when you peered inside it was fully furnished in the most amazing detail. At bedtime every night the boat’s lights would turn on, and we’d go over to Troy’s bed and read him a story. Despite being strapped down 24/7 he seemed remarkably happy despite his circumstances, and we could tell he liked the stories.

During the daytime, Kevin and I devised a game to amuse Troy. His wheelchair was high enough that we could fall under it and run each other over in turn. He enjoyed that immensely.

One day after a visit to the main hospital to see Doctor Croke I returned to find Kevin and his boat gone. I was beside myself, but the nurse assured me knowingly that he’d be back, and so he was, just a couple of weeks later.

There are moments that have embedded themselves in my memory from that time. Little Samantha wheeling over to introduce herself to my brother and parents when they visited. Troy’s toothless smile when we made him happy, and the rather tragic vision of a mother staring hopelessly out of the window as she sat next to her comatose teenage son in the cot.

Another vivid memory makes me question just how long I was interned and I still don’t really know. There was a procession of children and nurses that I joined on the way to a little church on the grounds; kids trying to walk in calipers, and a girl whose head was so large it had to be supported by a shelf on the back of her wheelchair. A reminder that I should be grateful for being able to walk unhindered. I can’t remember what the ceremony was, but I think it may have been Easter.

The time did come when I was allowed home for the weekend, and I felt elated. It was a test run, and I had to return on the Monday, but I actually felt ‘normal’ again. I went to the local corner shop and bought small gifts for my family with my pocket money, just to show that I appreciated them. I know that my previous behaviour had made life very difficult for them all; especially my mum who I’d brought to tears many times.

The test went well and after a couple more home visits, Doctor Croke decided her job was done and signed me off, although part of the condition required my Mum to get rid of all of my comics from my sacred comics cupboard. The thought of this was unbearable for me, but there was no other choice. In retrospect I have a strong feeling that Seduction of the Innocent (1954), Fredric Wertham’s sociological and psychological report which concluded that comic books were a harmful form of popular literature for kids, may well have played a part in that decision. Luckily, my Mum didn’t throw them away, but gave them to my childhood friends, which meant I was eventually able to swap most of them back again, albeit not in their previously pristine condition. This was thankfully no longer a concern of mine… because I was cured!

It’s pretty ironic that I’ve ended up spending most of my working life in the Comics business, especially as the Doctor apparently confided in my mum that she thought I’d end up being a man of the cloth. This makes me curious, and I wonder what led her to that conclusion. Was it the struggle between good and evil of the voices in my head? I just don’t know, and thankfully they’d dissipated entirely. Religion certainly has its own set of distinctive rituals, so perhaps it was because I’d created rituals for myself, to protect me from intrusive thoughts and some kind of presence that had manifested itself in our home. This was of course a disturbed house located next to a Black Death plague pit that I’ve mentioned previously.

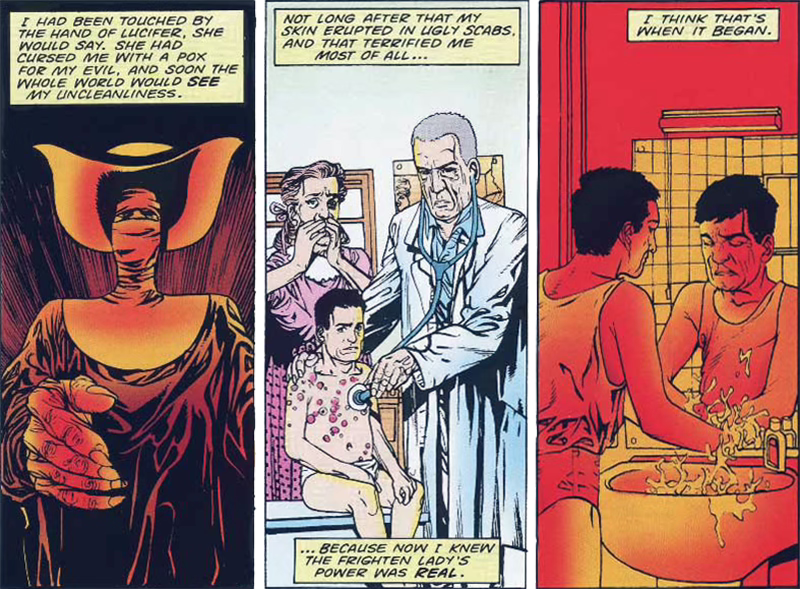

I’m also curious how this behavior was triggered. It’s a shame I didn’t get to discuss it more with my parents, but I think we’d all drawn a line under it, and it was best left in the past. There are a few, what I’d consider traumatic events that I can still recall. One was a terrible nightmare about a hideous old hag who put a spell on my younger brother, which gave him sores all over his body. Two days later he actually broke out with sores all over his body, and my parents had to take him to the doctor. I remember standing at the kitchen sink and washing my hands over and over again, feeling somehow responsible. I told my friend John Tomlinson about that a few years ago, and gave him free rein to use it in his Lords of Misrule comic (pictured), I mean we all suffer for our art, right?

There was also a vacation trip to Hayling Island and on the way there we stopped off in a small town. My parents figured at the age of nine I was old enough to use the public toilets on my own, but a few minutes later I came running out in fear, uttering something about a man in there who wasn’t human. Dad ran in to confront him, but there was nobody there. He confirmed this with me years later, but I know what I saw — in fact I was so scared that I hung on to my mum and kept looking at reflections in the shop windows to see if it was following us.

That same holiday there was a snake incident. Being inquisitive about nature I was thrilled to find a baby snake in the grass of the holiday camp where we were staying. I coaxed it into my hands and let it nestle there before taking it along to a children’s club event that morning. On arrival, the adult with the blue blazer who was leading the event took it off me hastily and held it up for all the children to see. He reprimanded me, and told us all that under no circumstances should we ever pick snakes up if we see them. Apparently it was a baby Adder, the only poisonous snake native to the British Isles. If that wasn’t bad enough he gripped it between his forefinger and thumb, just behind its head and choked it to death in front of us all. The sound it made was sickening and I felt so revolted and guilty that I was the cause of this poor creature’s suffering that it affected me deeply. I ran back to the chalet and washed my hands over and over, in case there was any poison on them.

Anyway, I’m certain that whatever the trigger was, it certainly wasn’t comics. There was a family who owned a grocery store in our road, and the back of their building was opposite our house. There were long wooden stairs that led up to their back door, and I would often sit at the top of those stairs with the grocer’s boy who was a fair bit older than me, looking at all his comics and Monster magazines until the sun went down. It all seemed magical. I believe it was he who originally introduced me to Marvel comics, and they were usually stashed in his school satchel. He also introduced me to his Aurora Frankenstein Monster kit, and his amazing collection of mould and spores that he’d been cultivating in plastic containers; not quite up to The Last of Us standards, but they were pretty impressive.

That’s the end of this particular story. I’m happy to say I’m better now, and have been for a very long time. I’ll always be incredibly grateful to Doctor Croke for that. There is a reason I decided to write about this. Living in America, I know that a large proportion of the population tend to go to therapists. It’s kinda normal — but since my childhood, I’ve never felt the need, until I decided to book a session with a counselor during the pandemic. Some of my childhood behaviors began to resurface, and I didn’t want to go down that road again. By the time I got to talk to the counselor though, I’d figured it all out for myself, so I told him this story and my own conclusion.

It’s almost as if I’d prepared myself as a child to exist in the constant fear of being infected, but this time it was a very real threat. It was Covid-19. I knew how to wash my hands a zillion times, how to hold my breath if needed, and how not to get infected during the entire Lockdown. However there was also an office move and the instruction to clear our offices of all our publications and comic books, and suddenly it dawned on me. Not only was I battling contaminants again, I was losing my comics cupboard. The past was a great big echo!

The counselor said “Wow, I think you’ve hit the nail on the head, and I’ve actually learned something myself today. I think you should write about this and share it, because shared experiences can be a great help to anyone suffering similar problems.”

So now I have, and I can go back to my regular Secret Oranges posts. ◡̈

I remember you telling me about some of those behaviours, which was very brave at the time due to the stigma attached to mental health.

Your spell in hospital must have terrifying for a 9 year old boy. Certainly glad you made a full recovery.

Wow. Thank you for sharing those memories, Steve. Powerful words. Mental health is so precious. We’re so unaware of what others are facing under their “public” face.